War as a Challenge for the Christian Vision:

Christian Harmony and Discord in Time of War

SERGEI CHAPNIN AND REV. MATTHEW BROWN

Church of the Ascension in Lukashivka village / Григорій Мазур / АрміяInform

How should we as Orthodox Christians respond to violence? More specifically, to what extent, if any, should we support and justify violence? Is this ever necessary or permissible?

For the last year and a half, since the outbreak of war in Ukraine, many of us in the Church have found these questions inescapable. They’ve produced ever-widening rifts in the global Orthodox world. All told, the responses that have emerged could be grouped into three major camps. They are:

1) We should just pray for peace

2) This war is justified

3) God has condemned any use of violence

Is one of these positions the “right” Orthodox position? Is that even the right way to frame this moral problem? We will examine each one of these positions and see whether any of them can be supported by our tradition.

1. We should just pray for peace

It’s not uncommon to hear the statement, "The Church should not be involved in politics.” Since the start of the war in Ukraine, it’s been amplified among some circles of hierarchs and clergy. It’s often accompanied by comments like “We do not need to understand the political reasons for this war. Our task as Orthodox Christians is to pray for peace.” Prayers for peace were composed in a number of local Orthodox Churches shortly after the Russian invasion began. Both the Russian Orthodox Church and the Orthodox Church in America prescribed these prayers to be recited each at the end of each liturgy, as well as in special petitions in the Litany of Supplication.

However, in the case of the Russian Orthodox Church, it’s safe to say that these prayers, to put it amicably, have been part of a public relations effort on behalf of the Kremlin. They’re clearly not politically neutral; instead they exploit the natural desire for peacemaking that many Christians share. They’re like an ideological parasite on a theological host.

Take, for example, what is now commonly being called the "prayer of Patriarch Kirill” which neatly aligns with the current ideology coming out of the Kremlin:

“From the one baptismal font at the time of the holy Prince Vladimir, we your children have received grace - establish a spirit of brotherly love and peace in our hearts forever! To the foreign nations, who would seek to fight and to attack Holy Rus', forbid, and overthrow their designs.”

The first takeaway, then, is that we should beware of those who would use prayer and peacemaking as cover for ideology. Prayer, when co-opted for an ideological purpose, can be used to halt any judgment of moral culpability, as well as for the starting, escalation, and prolonging of a war. It can stifle us from making moral judgments about the parties responsible for driving the conflict, and no party foreign or domestic is free from such responsibility. Prayer must accompany and strengthen the church’s prophetic voice to call all the worldly powers involved into this conflict to account.

The truth is that this prayer and much of the rhetoric associated with it ignore the reality of Ukrainian cities and towns being decimated by Russian missiles, thousands of civilians being killed, and tens of thousands of Ukrainian children being kidnapped to Russia, not to mention hundreds of thousands of young Russian men dead or injured. Can this behavior of the Russian government—and the Russian Orthodox Church that supports the war—be called brotherly love? Is this what genuine desire for peace looks like?

Visit of patriarch Bartholomew of Constantinople to Russia, May 2010 / Russian Presidential Press and Information Office

This brings us to another question. Suppose the admonitions to “only pray for peace” are sincere. In that case, what are we to make of them?

On one level, prayer alone is not sufficient. We are also called to moral action as Christians. Think of Christ’s parable of Lazarus and the rich man, found in the Gospel of Luke. The rich man encounters Lazarus, a beggar, lying at his gate. He ignores him, not even offering him scraps. If he had prayed for Lazarus, this still wouldn’t have been enough. It wouldn’t have conformed to Christ’s instructions about how to treat “the least of these.”

In the same way, praying for peace cannot be a substitute for right action, but rather a constant companion on the road of working for peace. This doesn’t mean the Church needs to involve itself in political negotiations (although it has sometimes played a valuable role in that arena). But it does mean Christians should think creatively how they might help. The work of Dr. Paul Gavrilyuk and his team at Rebuild Ukraine, who deliver aid to suffering Urainians, is one possible model.

The more difficult question is what we mean by “peace.” Should we be praying simply for violence to stop? Or does a Christian vision of peace demand more than this?

If we examine the paschal hymns, we see that Christ’s action on the cross, his harrowing of hades, and his resurrection are all cast in the poetic language of conflict. Christianity is not a faith that avoids conflict; rather, it redirects it towards the true enemy: sin, the Devil, and death. These are the “principalities and powers of darkness” that St. Paul speaks of. The appropriateness of violence is another subject, but as to whether conflict is ever justified, the answer is a resounding yes. Real, lasting peace is not a mere ceasefire, but a just resolution.

In many wars—and the conflict in Ukraine is no exception—it’s easy to imagine a version of “peace” that simply amounts to the stronger party suppressing the weaker one, indefinitely. From a Christian moral standpoint, this is not enough. This is the third lesson we can draw regarding the “pray for peace” position: there is no true peace without justice.

2. This war is justified

In any given conflict, it’s common for Christians to adopt some version of the just war theory. For many, this position isn’t the result of rigorous theological engagement; it’s simply the idea that any violence committed by their own side is justified in the eyes of God—that their hands are clean. This position has been widely adopted on both sides of the Russia-Ukraine war.

The just war theory in a primitive form was first articulated by Saint Augustine of Hippo in the 5th century and later refined by Thomas Aquinas in the 13th century. In his essay "Against Faustus the Manichean," Augustine asks the question, "What is sinful about war?" He answers in this way:

“The real evils in war are love of violence, revengeful cruelty, fierce and implacable enmity, wild resistance, and the lust of power, and such like; and it is generally to punish these things, when force is required to inflict the punishment, that, in obedience to God or some lawful authority, good men undertake wars, when they find themselves in such a position as regards the conduct of human affairs, that right conduct requires them to act, or to make others act in this way.”

One might see this position reflected in the prayer of the Orthodox Church in Ukraine:

“By Your might strengthen our godly people, bless their deeds, increase their glory with victory over the enemy, strengthen our state with Your almighty right hand, preserve the army, send Your angel to strengthen the defenders of our people, give us all that we ask for salvation; reconcile enmity and establish peace.”

This prayer is not merely asking for an unspecified peace; rather, it is asking for a peace achieved through victory—as victory is seen as a necessary and justified step toward lasting peace. But we should ask, what exactly is the standing of the “just war theory” in the Orthodox tradition?

A lucid answer can be found in For the Life of the World: Toward a Social Ethos of the Orthodox Church, a document issued by the Ecumenical Patriarchate in 2020. It says:

The Orthodox Church has also never developed any kind of ‘Just War Theory’ that seeks in advance, and under a set of abstract principles, to justify and morally endorse a state’s use of violence when a set of general criteria are met. Indeed, it could never refer to war as ‘holy’ or ‘just’. Instead, the Church has merely recognized the inescapably tragic reality that sin sometimes requires a heart-breaking choice between allowing violence to continue or employing force to bring that violence to an end, even though it never ceases to pray for peace, and even though it knows that the use of coercive force is always a morally imperfect response to any situation. … Christian conscience must always reign supreme over the imperatives of national interests.”

The just war position can easily become a fiction to justify actions that are unjust. It can also lead Christians to believe that in cases where violence is necessary, their own hands are clean and their souls free of any culpability. In reality, no such pristine position exists. Self-righteousness and the proliferation of violence are real dangers of this position, as is blindness to one’s own moral failures committed during a time of war for which an individual or entire people must repent of, and make recompense for.

3. God has condemned any violence

Finally, there are those who believe Christian peace precludes any kind of violence. This position is perennial in the Orthodox tradition. Christian theologians from the pre-Imperial age of the Church can easily be cited in support of this position. Take Tertullian’s brief but capacious formula, written in the second or third century:

“For albeit soldiers had come unto John, and had received the formula of their rule; albeit, likewise, a centurion had believed; still the Lord afterward, in disarming Peter, unbelted every soldier.”

This opposition to state-sponsored violence, however, is not restricted to the pre-Imperial age. It can also be seen in St. Ambrose’s standoff with the Emperor Theodosius in 390. That conflict began when Emperor Theodosius ordered the murder of seven thousand citizens of Thessalonica at the city's hippodrome. When the emperor went to the liturgy in the cathedral, St. Ambrose did not let him even into the narthex of the church. Saint Ambrose excommunicated the emperor for eight months, and the emperor accepted this penance. He entered the church and received communion only on Christmas in the year 391.

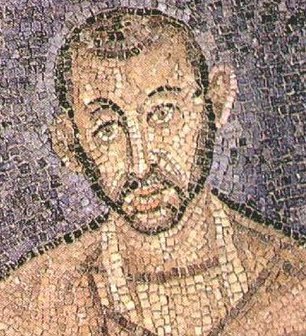

Saint Ambrose of Milan / Wikimedia Commons

However, despite these precedents, pacifism has not been the prevailing position in the Orthodox tradition. Christian pacifism is a kind of maximalism, and it’s hard to make this position work in an absolute way while being faithful to our tradition. An inflexible and absolutist ethic is rarely found among the writing of the saints. It is more common among rigorists and schismatics, such as the Novatians, a sect that existed from late antiquity until the eighth century, who believed that any fellow Christians who betrayed the faith under threat of persecution should not be readmitted into the church.

What distinguishes this approach from the rest of tradition, given that we regularly venerate martyrs and passion-bearers who willingly sacrificed their own lives? The difference is that most Church fathers and martyrs have not called for an absolutist standard of pacifism, one that is binding upon all Christians for all times - though it ought be stated that even if our tradition has not unequivocally adopted a pacifist ethic it has certainly adopted an ethic of peace and strong skepticism towards war.

Moreover, we have to be careful about espousing pacifism from our comfortable position in the West, far removed from the devastation in Ukraine, insulated from the difficult personal choices that people have to confront in the face of violence against those dearest to them. To condemn all violence when we’re not in the position of having to accept martyrdom is not necessarily virtuous. These moral questions have a personal dimension that shouldn’t be ignored.

* * *

How, then, should we respond?

First, we should recognize that an easy and tidy response is not readily at hand—and that to think otherwise is dangerous. Second, we can safely say that mere prayer is not enough. If our prayers never touch the rest of our lives and shape our actions, what kind of prayer is that anyway? Third, we should be cautious about declaring any war just. Declarations like these can easily lead to defending atrocities. Wars are complex, and in some cases, military actions that are justifiable can be used as a smoke screen for defending actions that are reprehensible. However, we also need to accept that sometimes ethically imperfect options are the only ones we have. In those cases, we still have to repent and make amends for our choices – even if those choices were in large part handed to us by the circumstances.

Finally, we should recognize that absolutist ethics such as pacifism tend to oversimplify complex problems. They overlook the personal dimensions of moral choices, and ignore the moral burdens placed upon each of us to discern what is good in each situation. In some areas, the question of what is right does not come down to a single rule that applies in every situation. Further, such absolutist ethics are an easy temptation for those who don’t have to contend with its costs.

All this is to say that there’s no perfect answer. Unfortunately, to give some kind of step-by-step instruction on how to be the most Orthodox with regard to the war in Ukraine would be misguided. At this point perhaps the best we can do is identify moral and intellectual pitfalls. This is more of a negative ethic, like negative, or apophatic theology. The ethical life of a Christian is always this way: it requires us, individually and together, to discern in an ongoing way what seems to be the most Christ-like path, in the context of a fallen world. And the best way to do that might just be identifying all the wrong ways, instead of the one right way.